Verbal Diarrhoea at Microsoft Surface Pro 3 Event

Yesterday’s Microsoft Surface Pro 3 launch event showed off what I think is a fairly compelling product. If what I really wanted was a single device that could replace the more specialised devices I have in my MacBook Pro and iPad Air, and if I thought I’d enjoy using Windows 8, then the Surface Pro 3 would be a very tempting way to go. Personally I don’t and I wouldn’t, so I won’t, but you might feel differently.

But apart from the product itself, two things really struck me when I watched the event video.

Software Is Hard

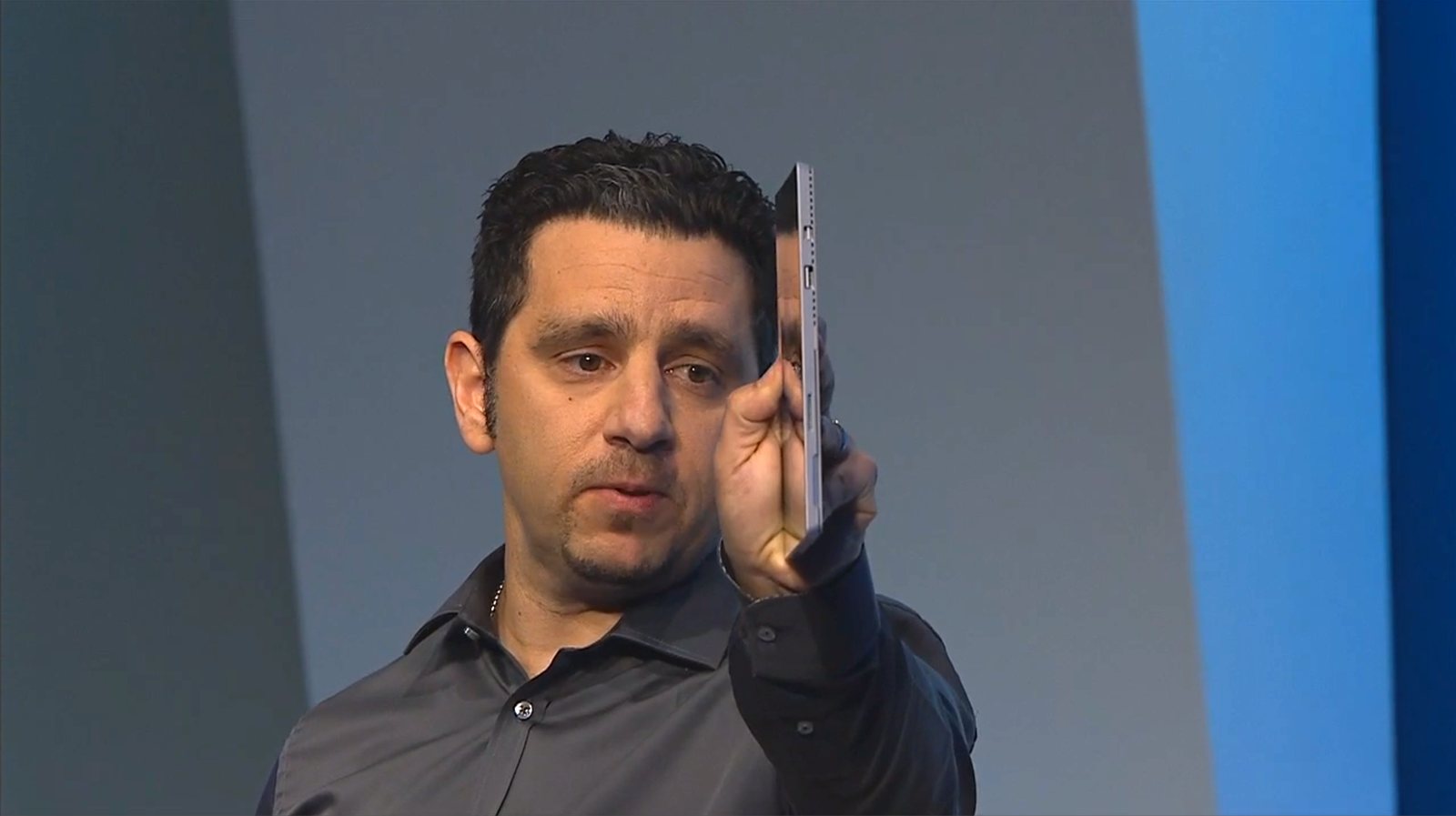

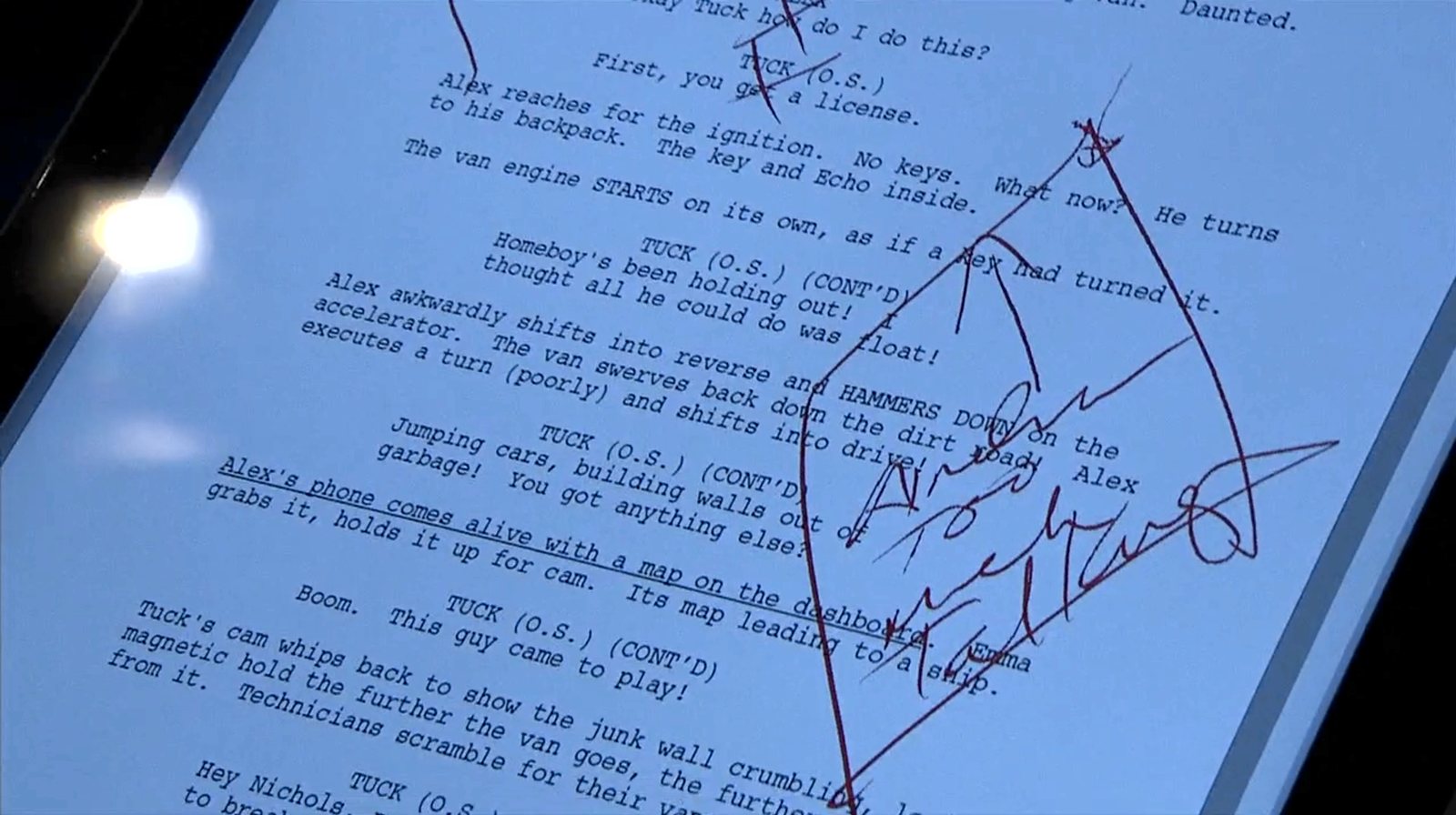

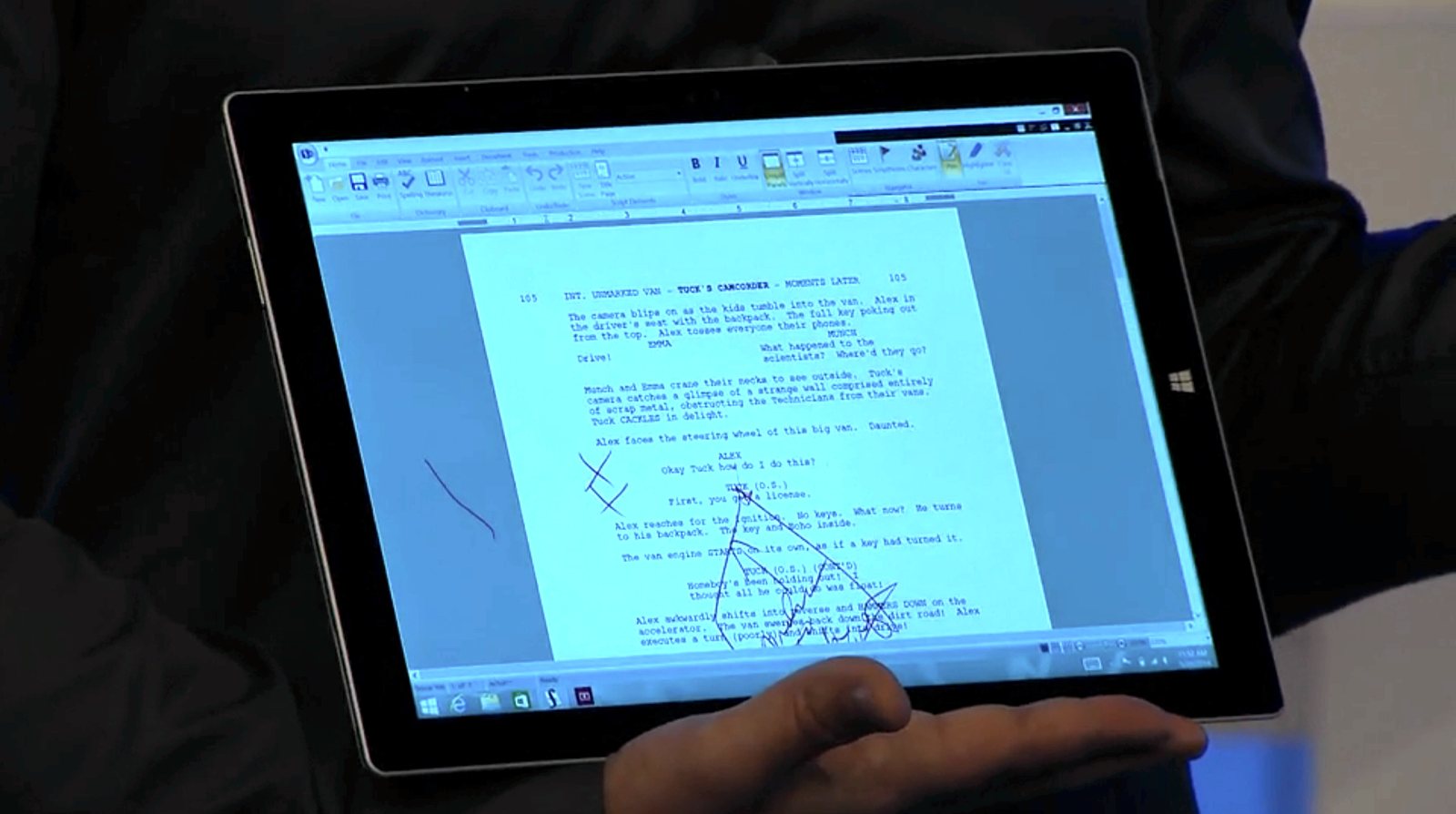

The first was the tell-tale signs of sloppy software. Much as Microsoft works to reinvent Windows to match the design pedigree of its chief rival Apple, no amount of visual polish can mask the fact that software is hard. Take the Final Draft demo, in which Panay demonstrated scribbling handwritten notes on a screenplay.

After crossing out a couple of lines of dialogue and adding a comment with an arrow pointing at the relevant portion of the text, Panay then made a show of turning the device into landscape mode to show off the display. Unfortunately, this highlighted a flaw in the preceding demo—a flaw that was plainly visible to everyone watching for many long seconds while he spoke about the quality of the image. Can you spot it?

The handwritten notes no longer line up with the text beneath. Whether due to a bug in demo-quality software, or because Final Draft’s support for handwritten notes is simply more limited than Panay would like to have us believe, this moment highlighted to me the fact that Microsoft’s platform still can’t offer the polished experiences of its rival’s. (That said, Apple is having trouble living up to its own standards these days.)

Yes, software is hard.

Speaking Is Also Hard

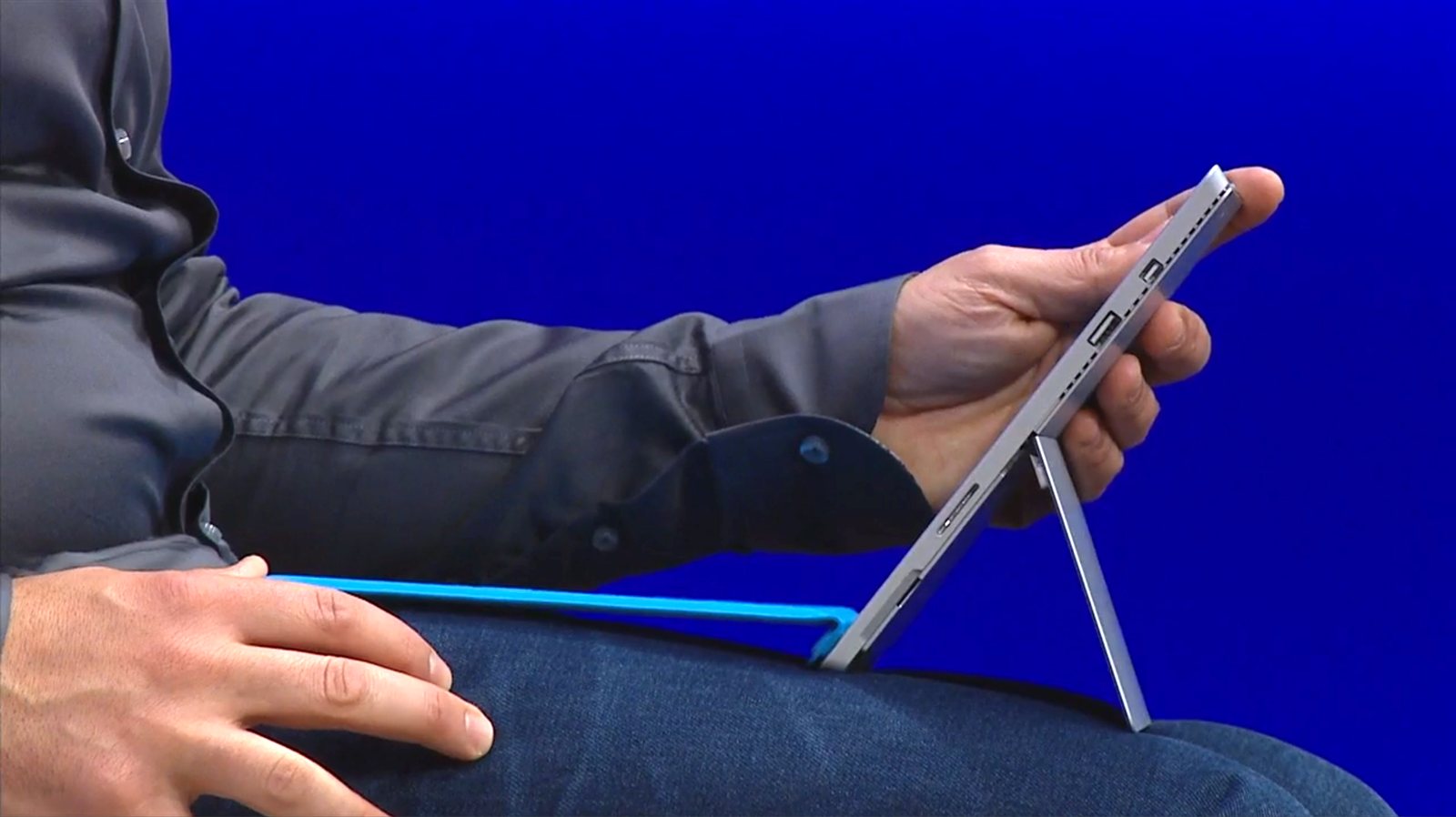

The second thing that stood out for me was presenter Panos Panay’s tendency to slip in and out of what my high school English teacher used to call verbal diarrhoea. Here’s a relatively mild example, where Panay is demonstrating how the Surface Pro 3 achieves improved stability when using it on your lap:

“And the reason is because you get this looseness in your hinge. And when you’re typing you kind of have to feel like “where should I put my—” and there’s too many thoughts. And when you put too many thoughts in a customer’s head, or a person who’s using its head, you really do find a place where they get stuck. And when you’re thinking too much when it should be that simple, it doesn’t work. It’s one of the beauties of tablets. It’s one of the beauties of laptops.”

You can get his meaning—mostly—from the context, but half of what he’s saying makes no sense. In an almost subliminal way, this makes the audience feel that the presenter doesn’t really care about what he’s saying, because he isn’t bothering to say it clearly. It comes off as stream-of-consciousness blather—verbal diarrhoea.

As a seasoned presenter myself, I know the irony is this can happen because you care too much about doing a good job conveying your message. There may be two causes for this:

- He’s nervous. Press events like these are high-pressure affairs. It’s not uncommon to see corporate executives, whose core competency is to stand in front of a room full of people and make a persuasive argument, to have visibly shaky hands. (Check out Adobe’s VP of Design Experience Michael Gough attempting to draw a smooth line in Photoshop during this event.) Nerves can also give you a “shaky brain”, which will cause your words to come out a little scrambled.

- He’s over-rehearsed. It’s no secret that these events are heavily rehearsed. There are some great behind-the-scenes stories from Steve Jobs’s gruelling rehearsals before Apple press events. One of the things professional speakers must wrestle with is the tendency to get bored of their own message. If you give the same performance too often, your brain can switch into auto-pilot, and start to let the details slip. Worse, your bored brain might amuse itself by trying to come up with better ways to say things on-the-fly, and you end up saying a mangled version of what you had rehearsed to perfection.

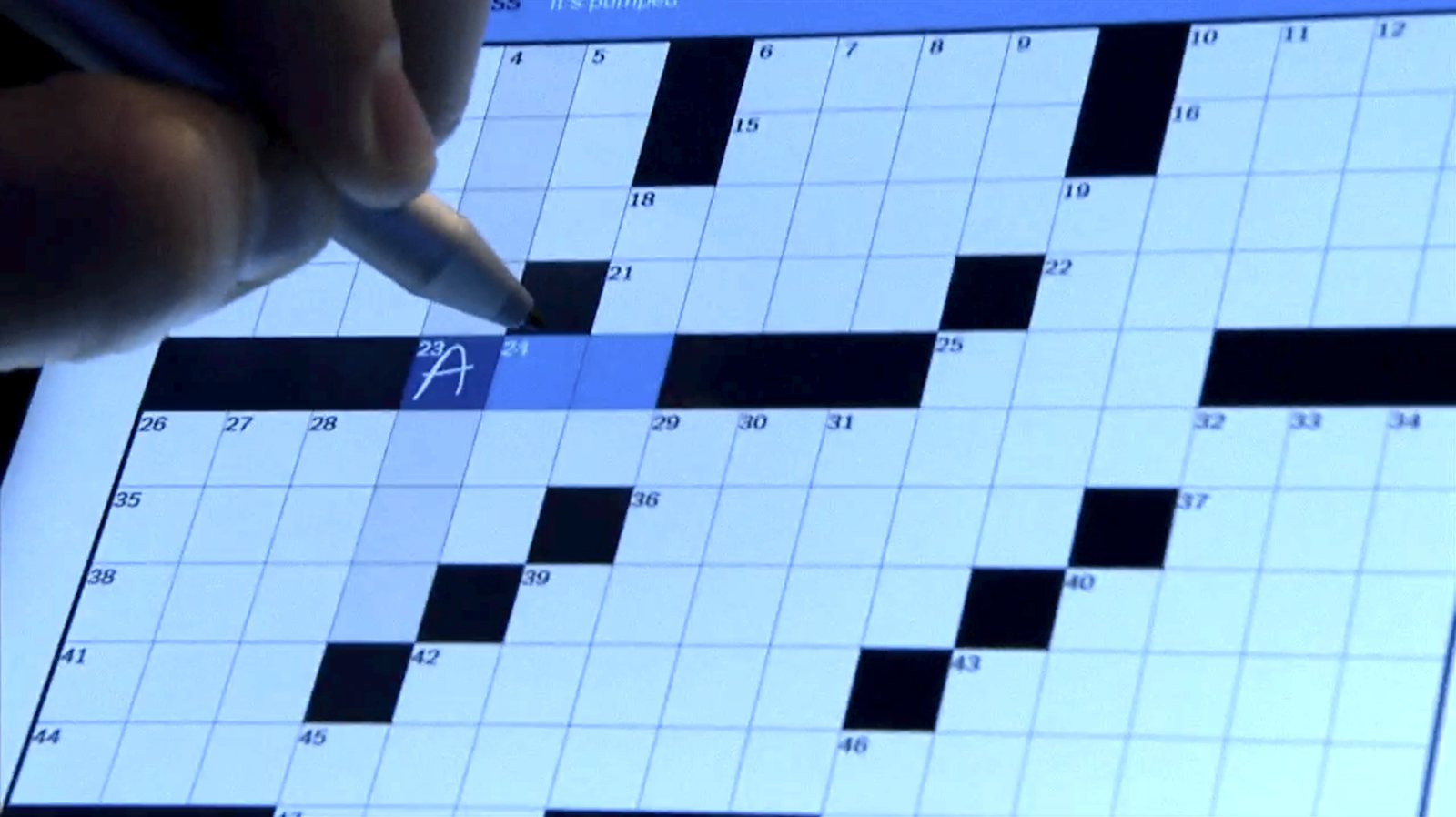

Here’s another example, from when Panay demonstrates how the New York Times Crossword app takes advantage of the Surface Pro 3’s pen input:

“And watch how I personally write it in. This is my handwriting, as I write it. Now watch how it transfers itself to actual digital content; did you see that? That’s important. We took nothing personal away in showing this app. Yet we’ve gone from an analogue to a digital place, which is so critical in making that feel seamless. Pretty cool.”

Panay was trying to make a subtle point, here. I’m sure it had something to do with an experience based around my own handwriting creating greater intimacy than other input modes can offer, and the unobtrusive handwriting recognition not interfering with that. I’m sure there was a script written to convey that idea with just the right words, but either through nerves or over-rehearsal, Panay made something up on the fly that was mostly nonsense punctuated by meaningless fluff like “That’s important.” and “Pretty cool.”

Is there a cure to verbal diarrhoea? Well, you can start by figuring out how much rehearsal strikes the right balance for you, as a speaker, so that you hit the stage neither under-rehearsed (which will make you nervous) nor over-rehearsed (which will make you bored).

But even more important is to care, really care about what you’re there to talk about. You need to get yourself to a place, mentally, where you care more about what you have to say than you care about whether you do a good job saying it. You can spot presenters who do this by how they handle it when things go wrong. Does the demo crash? Does the projector go ‘pop’? Does someone set off the fire alarm halfway through the talk? If the speaker’s response is less “Oh god, it’s all come apart!” and more “OK, but I want you to get this anyway, so listen…”, you know they care more about conveying the message than about nailing the presentation.

Here, to me, is a clear instance of Panay focusing too much on the presentation, rather than the message:

“If the design point is something as simple as “we believe what can be digital will be digital”, you have to start removing barriers of technology very quickly. A piece of paper and a pen is as analogue as it gets. It is as natural as it gets. The design points through the device shine through. When you lay it down it feels like a piece of paper; you can write on it at any given time. You can move it and use it to replace your 13" laptops very quickly, yet then you can obviously use it as a tablet any time. But ultimately, removing that barrier of technology is critical to make it feel great. Critical. But how?”

This is just a bizarre mix of jargon (“design points”), obvious lines from the script (“what can be digital will be digital”), and the scattered remains of a dramatic device (“it’s as simple as a piece of paper”). What is entirely lost is what Panay was actually trying to say. When I hear a word jumble like this, it’s clear to me that the presenter is completely disconnected from his message, and is just trying to hit all the points of reference his stressed brain can remember from rehearsal.

Conversely, when Panay spoke near the start of the show about taking away the conflict that consumers face when deciding to buy a tablet or a laptop, it was clear to me that his message was on his mind. He spoke loosely but clearly, reinforcing his point with every remark, rather than muddling it. This was the high point of his presentation.

Caring first and foremost about your topic combats verbal diarrhoea by focusing your brain on the source of the words you want to say, rather than on the words themselves. You don’t get bored with the script, because the script’s not on your mind; the point you’re trying to make is.

Panay’s presentation style is compelling in so many other ways. His calm demeanour and authoritative tone demand attention. He makes eye contact with every part of the room. If he can get rid of that verbal diarrhoea, he might just get me to buy another Microsoft product one day.